Drawing on earlier work that has examined scientific models in a historical perspective,1 with particular attention to physics, this article turns to models in economics and sociology. In this perspective, the aim is less to offer an exhaustive typology of models than to sketch out a general interpretative framework – a conceptual toolbox – for analysing the way in which modelling in economics and sociology frames our understanding of the social, of politics, and of the economy.

According to the economist Bernard Walliser, and in comparison with the natural sciences, “Models are far less pervasive in the human and social sciences; there they appear as isolated islands within a broader body of knowledge. They are difficult to distinguish from theories, except by their resolutely formalised and idealised aspect. They intervene in fields where there are numerous statistical data over a long period (models of education in sociology). […] Economics (together with linguistics and demography) is something of an exception among the social sciences in that it uses models on a massive scale.”2

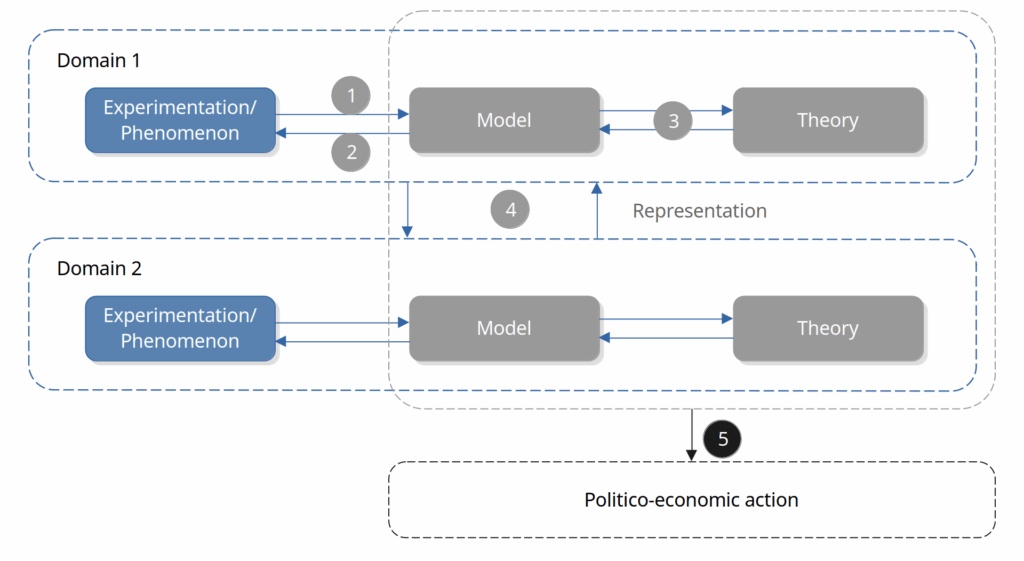

If models are more widespread in economics than in sociology, where theorising tends to be more conceptual,3 it seems to me worthwhile to consider these two disciplines together for three reasons. First, economics and sociology employ similar formal tools. Second, their types of modelling embody two methodological orientations: individualism and holism. Third, since models occupy a central place in the natural sciences, observing their use in the social sciences makes it possible to ask to what extent they are genuinely scientific.

From this angle, we shall first distinguish two major types of formalism, and address the issue of theoretical parameters. We shall then examine the scientific status of models, in particular by drawing attention to a number of controversies in the philosophy of science. Since this article provides an opportunity to sketch a conceptual synthesis of modelling in the sciences (not only the social sciences), a list of the functions of models, summarising the inventory drawn up by Franck Varenne,4 is supplied in an appendix.

Two broad types of formalisms

We can distinguish two broad types of formalisms for modelling in economics and sociology. The first, and most widespread, is based on mathematics, in particular algebra, differential calculus, and statistics. It makes it possible to highlight connections or differences between variables (or factors), and to describe how they evolve.5 The second rests on algorithms, especially those used in computing to describe, among other things, the evolution of processes.

These two families of formalisms are not watertight categories but ideal types, in Weber’s sense: in practice many models combine mathematical equations with algorithmic procedures, and some frameworks – such as game theory – circulate between the two. Each benefits from advances in computing, which make it easier both to perform complex calculations and to simulate individual and social phenomena.

Mathematical formalisms

Mathematics started to be used to build models around the 1920s–1940s.6 Until then, they had served mainly to formulate the theories and laws that researchers were seeking. Statistics were already being used at the beginning of the 20th century by Durkheim in his study of suicide; we can also mention the work of Francis Galton and Karl Pearson (late 19th–early 20th century), who contributed to the development of statistical methods. Galton, in particular, coined the term “linear regression”.

It is worth noting the coincidence between the use of mathematics in modelling and the development of the term “model”, which emerged “simultaneously, in 1936–1937, among economists and statisticians, very often trained as physicists, such as Jan Tinbergen, Eugène Slutsky, George and Edouard Guillaume, Abraham Wald, Jean Ullmo, Jacob Marschak, Trygve Haavelmo, Jerzy Neyman”.7

The discipline of econometrics, born in 1930 with the creation of the Econometric Society by Irving Fisher and Ragnar Frisch, played an active part in developing models using statistical tools such as linear regression, lagged models, time-series analysis, and so on. For example, in microeconomics, the relationship between a household’s housing expenditure E and its income I can be expressed in the form of an “affine relation (E = E₀ + a*I), where E₀ is the minimum expenditure independent of income and a the fraction of income devoted to housing”.8 In this simple linear regression model, E is the variable to be explained and I the explanatory variable.

A much more elaborate economic model, this time in macroeconomics, is Robert Solow’s model of economic growth (1956), which comprises five equations:

- a production function;

- an accounting equation for GDP;

- an equation for savings;

- an equation for the evolution of capital, which is a differential equation;

- an equation for the evolution of the labour force.

In sociology, models appear in the 1950s, particularly in research on social mobility (Bendix and Lipset, Dahrendorf).9 In this connection, and by way of example, one can recall Pierre Bourdieu’s conceptualisation of “social space”, which rests on the notion of “capital”. In La Distinction (1979), he provides a “simplified model of this space, based on the knowledge acquired in earlier research and on a set of data taken from various surveys”.10 To construct this panorama, he makes use of several correspondence analyses, exploratory statistical methods that make it possible to study links between several variables.

Overall, mathematical models bring out links or differences between quantitative variables (price, capital, age, etc.) and/or between qualitative variables (preference, habit, social category, etc.). The variables, or factors, are used to characterise sets of individual behaviours and sets of individuals. The relationships between variables are underpinned by statistical techniques.11

Algorithmic formalisms

Algorithmic formalisms make it possible, most often by means of computer implementation, to model dynamics and processes broken down into a sequence of stages or operations which, in economics and sociology, are frequently decisions, individual actions, and interactions. They include in particular two approaches based on methodological individualism: Raymond Boudon’s “generative models”12 (interesting for their innovative aspect in France in the 1970s) and multi-agent models,13 which have been developing since the early 1980s.

In L’inégalité des chances (1973), Raymond Boudon proposes an approach that is more complementary than competing with that of Pierre Bourdieu and Jean-Claude Passeron on educational inequalities and social mobility. Criticising “factorial theories”14 and the emphasis on cultural inheritance, he develops, for education, a model of the successive orientations (end of primary school, end of secondary school, etc.) of cohorts of students. These orientations are called “decision fields”, and here they depend more on “social position” than on cultural capital. Social position influences the choices made by actors at each decision point: “the action of social position is not unique, but repetitive. It generates multiplicative, or more precisely, exponential effects”.15

The underlying idea, which is also present in multi-agent models, is that models describing individual behaviours make it possible to grasp the emergence of phenomena. Boudon generally speaks of “generative mechanisms”, and in the case of education of multiplicative effects which, in his view, explain the formation of educational inequalities.16 Multi-agent models make greater use of computing power, whereas Boudon’s approach relies simply on probability calculations based on a list of axioms. They are associated with simulations.

One of the first multi-agent models, and no doubt the best known, is Thomas Schelling’s segregation model (1971), which brings to light unintended effects resulting from the uncoordinated actions of a set of individuals: “agents” of two different colours, representing households, are placed on a grid (a chequerboard in the reference model). They decide to move only if their peers become significantly under-represented in their “neighbourhood”. In the initial model, the homogeneous configuration in which neighbours of different colours alternate (as with the colours of the squares on the chequerboard) is locally stable, but becomes highly unstable as soon as it is disturbed. The system then converges towards a “segregated” configuration in which agents of the same colour cluster together in aggregates.17

Formalism, holism and individualism

Although algorithmic formalisms incorporate an element of methodological individualism, they can include mathematical formalisms and appear as complementary to them. In particular, mathematical formalisms make it possible to estimate variables and factors that can serve as input or output parameters for algorithmic models – for example, norms that influence agents’ behaviour, or whose emergence is observed through the study of collective action.18 In Boudon’s modelling of the school system, cultural inheritance is an input parameter.

Moreover, mathematical formalisms can be used to describe individual behaviours, as in the threshold models of the American economic sociologist Mark Granovetter.19 He illustrates this type of model with the phenomenon of participation in a riot: imagine 100 people gathered in a square and assign each of them a threshold for joining the riot (a person joins the riot once a threshold of N participants has already been reached): the first person has a threshold of 0, the second a threshold of 1, …, the hundredth a threshold of 99. With this “distribution” of thresholds, the first person triggers the riot, the second follows, then the third, and so on, and all 100 people end up taking part in the riot. In addition to this notion of a distribution of thresholds, Granovetter formulated a differential equation to predict how the crowd’s behaviour will evolve and whether an equilibrium may be reached, such as the participation of everyone in the square.

Looking at models according to their formalism (mathematical/algorithmic) makes it possible to articulate holism and individualism and to grasp the complementarity of approaches: individuals and groups, in algorithmic modelling, take into account holistic parameters (variables, factors) and also produce them as outputs – parameters that can in turn be related to one another through purely mathematical formalisms.

Formalism and causality

What is a social cause? A social force? An ideal type? A variable/factor used in mathematical formalisms, notably a group or a social category? An individual? A motive or a reason for action? These questions, recurrent in the epistemology of the social sciences since Durkheim and Weber – in other words, since the birth of these academic disciplines – continue to fuel lively controversies,20 particularly in France, where the presuppositions of political economy are regularly criticised within the social sciences.21

In the same way that I have emphasised the complementarity between types of formalism and between holism and individualism, I do not privilege any single type of cause. “Forces” such as selfishness and anomie, evoked by Durkheim in relation to suicide, can be considered as macroscopic factors associated with a historical and cultural context which, combined with a biological context, contribute to the emergence of psychological conditions that are more or less likely to lead to suicide. Each contextual element (cultural, psychological, biological, etc.) can constitute a cause. Even a social group, insofar as it is apprehended by actors as a unifying notion or a social bond, can be regarded as a social cause.

Is there not a tendency in the social sciences to restrict causes to a limited set of entities? This trend22 appears both among advocates of a form of methodological individualism – who often insist on biological aspects and psychological biases – and among defenders of a form of holism, who stress cultural aspects. It can also be read in political and moral terms by distinguishing, on the one hand, adherents of the market economy, capitalism and neoliberalism and, on the other, their opponents. However approximate, even reductive, this distinction may be,23 it points to a fracture within the social sciences, mirroring political fractures.

Theoretical parameters

Let us, as far as possible, remain on epistemological ground. Whether or not they support a critical line of thought, models in the social sciences rest not only on formalisms but also on theoretical parameters.

Principles and axioms

In his Essays on the Theory of Science, Max Weber writes that “the scientific method of dealing with value-judgements ought not merely to confine itself to understanding [verstehen] and reviving […] the ends that are desired and the ideals which underlie them; it also sets out to teach us to pass ‘critical’ judgement on them. […] In setting itself this aim, it can help a person of will to become aware, by his own efforts, both of the ultimate axioms which form the basis of the content of his will and of the standards of value […] from which he starts unconsciously or from which he ought to start if he is to be consistent.”24

Has this recommendation, which is particularly interesting from an epistemological point of view, actually been followed? If formalisms require a certain number of parameters to be made explicit,25 we may wonder, in both economics and sociology, to what extent such a methodological orientation has really been adopted. As Mark Granovetter notes in Society and Economy, “Null hypotheses are most often unexpressed, hidden beneath the surface of most descriptions of the economy in the social sciences: by this I mean any basic supposition underlying the interpretation of human behaviour and social organisation – the conceptual starting point of researchers trying to understand any set of phenomena. These underpinnings of so many rhetorical formulations in the social sciences have a powerful psychological impact on those who are persuaded by one argument or another (as McCloskey so eloquently pointed out in 1983).”26

While I have used the term “hypothesis” in earlier works as synonymous with a premise,27 I would now prefer to reserve it for conjectures that will actually be put to the test. The moral principles implicit in social theorising are precisely not directly subjected to experimentation in the way that the fundamental interactions in physics can be; and even when they are explicit, one may doubt whether they can truly be validated through experiments conducted in a given social context, a context with which they are associated and whose historical stability may prove short-lived.

We can look more specifically at sociological principles by considering the conceptualisations of Durkheim and of Bourdieu, who grounded his analyses in a principle of structural struggles, in forms of domination that limit actors’ critical capacity. It was by calling into question the overarching position of critical sociologists28 that Luc Boltanski and Laurent Thévenot, in On Justification (1991), developed a “city model” based on explicit axioms (or moral principles). This concept raises the question of the extent to which a “city model” can be regarded as a sociological model.

In economics, the issue of the existence of a “homo economicus” has been discussed in connection with a set of theoretical parameters describing his more or less pronounced rationality. Linked to a form of rationality that induces greater co-operation, game theory developed from the end of the Second World War onwards—the prisoner’s dilemma is one of the most famous examples of a game. It “has established itself as a general ontological framework for strategic relations between actors of any kind. It has quickly come to be seen as the prototype of modelling in the social sciences and has been taken up in other disciplines.”29 As an “ontological framework”, game theory aggregates a set of theoretical parameters that enter into the construction of models. In practice, this framework can give rise both to analytical “equilibrium” models and to simulated or multi-agent set-ups that evolve strategic interactions step by step: it precisely illustrates the porosity between mathematical and algorithmic formalisms.

Idealisations and categories

Idealisations can be illustrated with Nancy Cartwright’s approach. We can distinguish Aristotelian idealisations (or abstractions) from Galilean idealisations, which deliberately deform reality. Abstractions and Galilean idealisations operate in both mathematical and algorithmic formalisms.

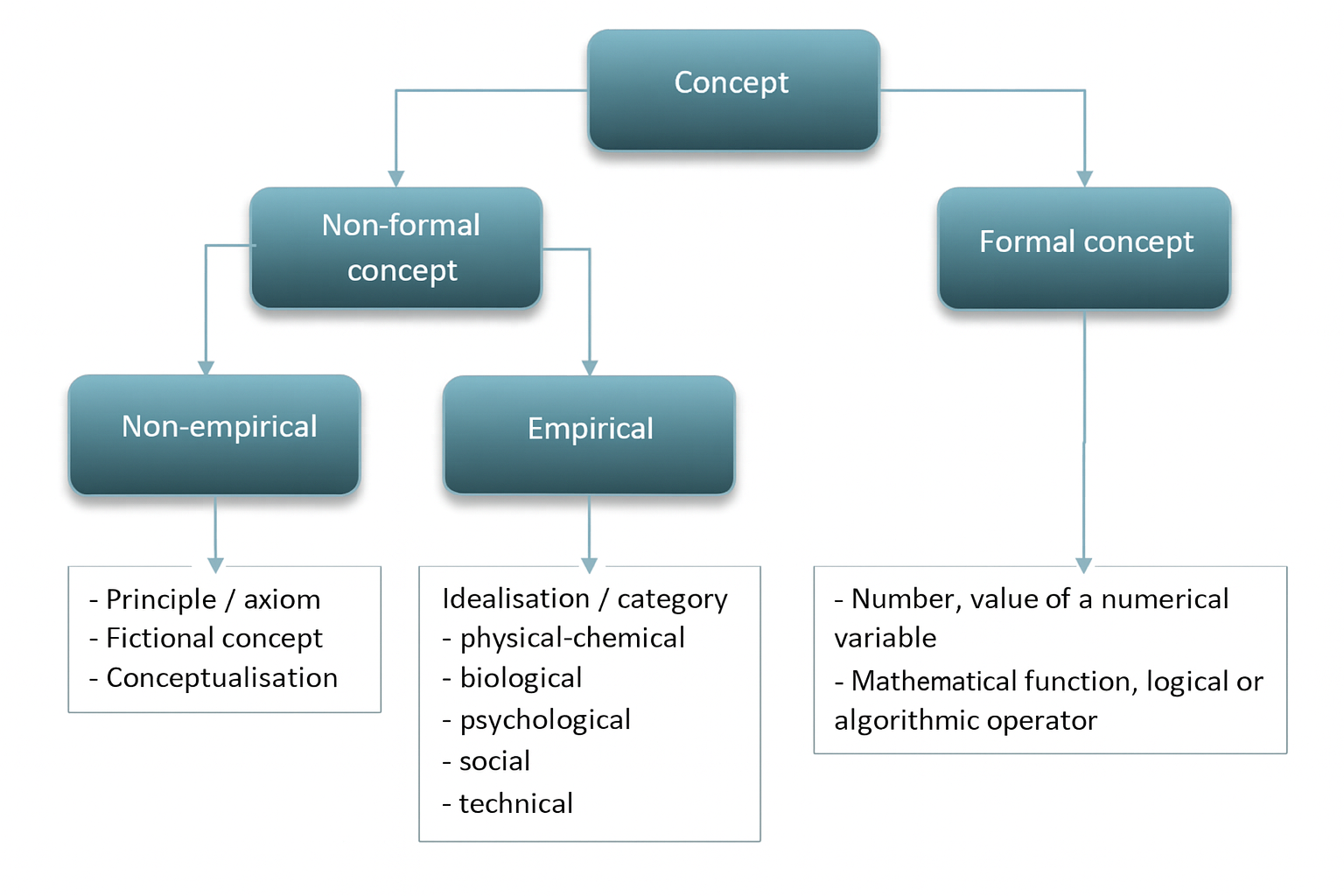

Reflecting on models in economics, particularly Robert Lucas’s model (1981), Cartwright has highlighted the use of “non-Galilean idealisations”: “most of the concepts used in these models are highly concrete and empirical.”30 Moreover, “the underlying theory is very thin. […] We have a handful of very general principles that we use in a non-controversial way in economics, such as the principle of utility theory.”31 Let us leave aside the idea that utility theory is non-controversial, for that is clearly not the case from a sociological standpoint; what interests me here is the concept of a non-Galilean idealisation, which seems to me to encompass two distinct types of notions: on the one hand principles or axioms, which are non-empirical; on the other hand categories and empirical idealisations of a physical, chemical, biological, psychological, social, or technical order.

Idealisations, which are more general than categories (the latter corresponding to the variables/factors in a formalism), here gather together abstractions and both Galilean and non-Galilean idealisations. They denote, for example: in physics, an atom, a colour, a force or energy, more broadly a unit of measurement (since the trajectory of an object is formal); in biology, a type of cell, an organic compound, an interaction; on the social plane, an institution, a group, a social category, a type of event, and so on.

Fictions and conceptualisations

Still drawing on Cartwright, fictions can be broken down into three forms: the models themselves, probability distributions in statistical physics, and fables. Despite its heuristic interest, the notion of fiction seems to me far too vague and literary to clarify scientific conceptualisations. Moreover, in everyday language the term “fiction” is opposed to “reality”. Yet the realities of the Earth and its surroundings are, to a large extent, shaped by human beings, particularly on the psychological and social levels. A strict opposition between fiction and reality therefore makes little sense in the human sciences. Modelling and theorising gradually clarify fictions by breaking them down into formalisms and theoretical parameters.

Principles, axioms, idealisations and categories constitute conceptualisations – a generic term that can describe a certain number of notions in sociology, as Jean-Michel Chapoulie notes: “Everyone agrees on the importance of conceptualisation in the social sciences, but what this term and its derivatives, ‘concept’, ‘conceptualisation’, ‘conceptual scheme’, actually denote is not precisely defined. The Trésor de la langue française offers the following definition of the first of these terms: ‘an abstract and general mental representation, objective, stable, accompanied by a verbal support’.”32 For example, habitus in Bourdieu or the “total institution” in Erving Goffman are social conceptualisations. In examining models, by limiting theoretical parameters to principles/axioms and to idealisations/categories, I am seeking to clarify matters while being aware, on the one hand, of the presence of conceptualisations within theoretical principles and, on the other, of their contribution to clarification, particularly through their heuristic value.

Limits to the scientificity of models

Emphasising action

Models can be considered (for example, by proponents of the semantic conception of theories) as the most exact formalisations we possess. But at best they constitute an approximation of reality, if not a fiction, for a pragmatic philosopher such as Nancy Cartwright. We can also cite the well-known aphorism of the statistician George Box: “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” Reflecting on models and bringing them to the foreground amounts to taking a certain conceptual distance from theories, which are global in nature and which, in the social sciences, especially in sociology (theories of Parsons, Bourdieu, Boltanski, etc.), fail, despite the insights they offer, to secure unanimity within the scientific community.

This stepping back from theories has gone hand in hand, in the second half of the 20th century, with a closer engagement with reality through the promotion of human intervention. In line with a pragmatic current now widespread in the sciences, from physics to sociology, the aim is less to ensure the truth of theoretical constructions than to design clearly the conditions under which we act (experiments with a theoretical purpose, politico-economic projects, etc.). This emphasis on action goes together with critical endeavours that consist in deconstructing traditional concepts and questioning politico-economic orientations. These tendencies can be observed in particular in the works of Michel Foucault, Nancy Cartwright, Ian Hacking, Bruno Latour, and Luc Boltanski.

For an action to be crowned with success, for an objective to be achieved, or for us to understand why it has not been, we need to know how to proceed. This is where the issue of causality comes in most directly. If models, whatever their formalism, make it possible to identify causes, these remain in most cases approximate, partial and hypothetical. To what extent can we say that causes have been identified? To what extent is a model valid? More generally, what degree of scientificity do models have?

In contemporary controversies – over economic policies, the management of health or environmental crises, the regulation of markets – these models act as mediators between knowledge and decision. It is rarely their structure that is discussed in public, but rather their results, even though their theoretical parameters (values, anthropology, definition of “rationality”) often remain implicit.

Inventory and stability of causes

While it is appropriate to distinguish the question of causality from that of validity, or corroboration – since some models are intended to be predictive whereas others aim to describe – it does not seem possible to corroborate a law or a model, however descriptive it may be, without the notion of causality, because any experiment takes place within a certain context that specifies a set of causes pertaining to the phenomenon under study. And outside the formal sciences, to conceive without experimenting is to place oneself in a Platonic heaven.

Knowledge and causality are entangled: any non-formal empirical concept can constitute a cause, depending on the context in which it is used. For example, oxygen is one of the causes of combustion; in the laboratory, the microscope can be one of the causes of perception; a leg is not vital, but it is one of the causes of walking, just as the heart, the brain or the psychological motive that leads us to move, a motive that may be wholly or partly of social origin (for example, going to vote, more generally complying with a norm, going to an appointment, etc.). Moreover, certain combinations of non-formal and formal concepts, particularly laws, can also be regarded as causes in so far as they make explicit limits to the evolution of a given phenomenon or system. I therefore assign to the notion of cause a broad meaning that excludes neither any existing approach in the philosophy of science33 nor any methodology.

The identification of causes takes place within a perspective that does not necessarily entail a kind of “instrumentality” or “utilitarianism”, in so far as establishing knowledge requires the manipulation and observation of causes. One of the main issues in the sciences concerns, more than the possibility of determining “a necessary and sufficient cause”, the possibility of specifying a context or set of causes within which a phenomenon described by laws and/or models occurs – in other words, to identify as exhaustively as possible the causes, among which empirical theoretical parameters are included. This is what the controversies surrounding statistical methods bring out.34 Have the factors or variables been identified exhaustively? Are they all observable? Are they independent? Are there possible confounding factors, that is, factors that are common to and/or antecedent to the identified causes? Can the inferences of a statistical study be applied to a context other than that of the study itself?

In the social sciences, an exhaustive inventory of causes often proves delicate, if not impossible. In addition, the definition of what constitutes a social cause, as we have seen above, is itself controversial. Let us note that a non-formal and non-empirical concept – for example, the concept of a house at the planning stage, or the concept of a mythical hero – is a potential cause in so far as it orients the action of actors, whether or not they are aware of it. This contributes to the conflictual and complex character of the definition of reality, in particular through political debates on draft laws and societal projects, through the specification of the social categories used by statistical institutes or polling organisations, and through the labelling of social groups and behaviours.

A few examples: (1) the definitions of republican principles (liberty, equality, fraternity) are the subject of endless philosophical dialectics. (2) INSEE’s nomenclature of socio-professional categories was revised in 2020, notably in order to take into account “changes in the detailed level of occupations: the spread of digital technologies; the development of activities linked to the ecological transition; convergence between occupations carried out by public-sector employees and those of private-sector employees”. (3) Faced with the diversification of family structures, the marketing category “housewife over 50” has given way to that of “person responsible for purchases”. (4) While the concept of race is non-empirical, the behaviours associated with it, particularly discrimination, are empirical.

The imaginary dimension of psychological and social concepts, linked to the human capacity for creation and innovation – a capacity that has been particularly developed and encouraged over the last two centuries – raises questions about the stability of theoretical parameters, whether changes in these parameters are moral, political or technological in nature. To the examples just mentioned one can of course add digital innovations (hardware, networks, applications, AI, robots…), which contribute to considerable social reconfigurations. The stability of theoretical parameters is also called into question by environmental and health crises, which encourage significant changes in behaviour, particularly at the economic level. Yet changes in theoretical parameters, especially in principles, may imply that formalisms – and thus models – become obsolete.

Production of empirical data

Beyond the inventory of causes and their stability, there are limits to modelling in the social sciences that stem from the production of empirical data and from its availability – empirical data correspond to numerical values associated with categories: the number of people belonging to a category, the measurement of a quantitative variable. Here I merely list a few of the limits commonly debated in the philosophy of science.

Before any survey or experiment, a research design is constructed. As Bourdieu, Passeron and Chamboredon pointed out in Le métier de sociologue (1968), “There is not even a single one of the most elementary operations in the processing of information, apparently the most automatic, that does not involve epistemological choices and even a theory of the object. It is all too clear, for example, that what is at stake in coding indicators of social position or in drawing the boundaries between categories is an entire theory, conscious or unconscious, of social stratification […]”.35 It is often said that concepts – particularly categories in the social sciences – are “theory-laden”. This holds for any type of survey or experiment, whether carried out by national or international statistical institutes or by research teams, academic or private.

In econometrics, “a limit to testability arises from the frequent scarcity of data capable of validating the model. Some observed magnitudes are recorded historically over very short series or result from exceptional surveys. Other magnitudes, although theoretically observable, are in fact observed only locally, namely at equilibrium. […] Laboratory experiments can in principle compensate for the lack of historical data. But they are rarely repeated identically, even though their duplication is always invoked as indispensable.”36

In sociology as in economics, if data are not available, supplied in particular by official institutes, it is possible to produce them by conducting a survey oneself or by subcontracting it. Nevertheless, since the sample can generally not be constructed by random sampling, as INSEE does, the “margin of error” in estimating the distributions of the original population cannot be measured.37 The same kind of difficulty arises when exploiting historical surveys.

Another limit “is due to the fact that responses obtained in questionnaire surveys, as in the processing of historical corpora, are almost always non-exhaustive. Response rates in questionnaire surveys are often far below what would be required to accord the results more than provisional confidence.”38 We should also mention the limit linked to assigning a given individual to a category, the boundary between two social categories often being far from clear-cut.

Validation of models

Once the empirical data have been collected, formal procedures are applied to them in order to obtain results that can be compared:

- with other empirical data, at a later stage in the case of predictive models;

- with other results obtained previously.

These comparisons provide elements of external validation.39 They depend in part on the possibility of reproducing experiments, which itself depends on the stability of the theoretical parameters and, more broadly, of the causes between two experiments.

Internal validation concerns the methodology employed, in particular aspects relating to the production of empirical data and to the application of formal procedures, whether mathematical or algorithmic. In the case of multi-agent models, this validation consists more specifically “in questioning the conformity between the specifications and the implemented programme.”40 In the case of statistical methods, there are multiple issues relating to internal validation, among them: the construction of variables resulting from the aggregation of quantitative data; the use of certain statistical methods rather than others; the rigour with which a given statistical method is implemented.41 Let us mention finally the wide-ranging debate – concerning, first and foremost, biology – around the significance threshold in statistical hypothesis testing.42 Is the Neyman–Pearson test reliable? Can a hypothesis be rejected if there is a 5% risk of being wrong? Should we not rather choose a 1% threshold?

Models in economics and sociology are particularly difficult to validate because they mobilise complex methodologies and formalisms, because they are not necessarily underpinned by a theory that provides a form of stability, but also because they proliferate. In economics, according to Bernard Walliser, “models are undergoing anarchic proliferation, which causes them to lose their power and originality. Modelling tackles every possible and imaginable domain without taking account of their deep specific features,”43 and displays a “lax drift”. If models abound, is this not in part due to the lack of theories that are sufficiently stable and recognised by the scientific community?

In their 1999 collective volume Models as Mediators, Mary Morgan and Margaret Morrison describe models as “tools”,44 as objects that are “autonomous” in relation to both the theories and the phenomena studied. From this point of view, formalisms can be regarded as mathematical, logical or algorithmic tools – techniques for obtaining information about phenomena. But if models are techniques, what of their scientificity? Can we describe as scientific a modelling whose theoretical parameters evolve to such an extent that the formalism becomes inapplicable, or a modelling whose results can be compared with empirical data only in very approximate fashion?

Despite these outstanding questions, it seems to me that, by distinguishing formalisms from theoretical parameters and by distinguishing between different types of concepts, the notion of a model in the sciences appears less confused.

Appendix: multiple functions

The concept of a model has multiple facets. Historically,45 it was used first and foremost in a prescriptive sense, then from the 17th century onwards it evolved towards a more descriptive role in the sciences.

A model can provide a representation of reality, can have a heuristic or instrumental aim, or a family of models can define truth in line with a semantic conception of theories. The philosopher of science Franck Varenne summarises46 the diversity of a model’s scientific functions in five broad categories:

- Facilitating observation and experimentation.

- Facilitating an intelligible presentation “via a mental representation, whether pictorial or schematic, or already via a conceptualisation and an interaction of concepts, a concept being a general idea that is well defined and applicable to certain real or realisable objects or phenomena.”

- Facilitating theorisation.

- Facilitating mediation between discourses, in particular between fields of study.

- Facilitating mediation between representation and action: decision-making, especially political decision-making in the case of epidemic management, and in cases where the model is “self-fulfilling”.

These broad functions correspond closely to those identified by Mary Morgan and Margaret Morrison in their 1999 edited volume Models as Mediators,47 which takes physics, chemistry and economics into account. They also largely overlap with those described by Bernard Walliser.48

This article was originally published in French in 2021.

Notes

1.↑ Articles not translated in English: https://damiengimenez.fr/interventions-fictions-et-techniques-chez-nancy-cartwright-et-ian-hacking/; https://damiengimenez.fr/discredit-et-valorisation-des-modeles-en-sciences-au-cours-du-xxe-siecle/; https://damiengimenez.fr/le-concept-de-modele-en-science-a-laube-du-xxe-siecle-eclaire-par-boltzmann-et-duhem/

2.↑ Bernard Walliser, Comment raisonnent les économistes, Odile Jacob, 2011.

3. On this more literary and conceptual dimension, see in particular Jean-Michel Chapoulie, Enquête sur la connaissance du monde social. Anthropologie, histoire, sociologie, France–États-Unis 1950–2000, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2017, chapter IV.

4.↑ Franck Varenne, ‘Histoire de la modélisation : quelques jalons’, Actes du colloque Modélisation succès et limites, CNRS & Académie des technologies, Paris, 6 December 2016. URL: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02495473/document

5.↑ The two main types of statistical methods used for modelling can be distinguished as follows: exploratory statistics (factorial methods, classification methods) and explanatory/predictive methods. See the introduction to Ludovic Lebart, Alain Morineau, Marie Piron, Statistique exploratoire multidimensionnelle, Paris, Dunod, 1995. For a more advanced mathematical treatment: Gilbert Saporta, Probabilités, analyse des données et statistiques, Technip, 2006. For an econometric approach: Régis Bourdonnais, Économétrie, Dunod, 2021.

6.↑ Franck Varenne, op. cit.

7.↑ Armatte Michel, Dahan Dalmedico Amy. Modèles et modélisations, 1950-2000 : Nouvelles pratiques, nouveaux enjeux in: Revue d’histoire des sciences, tome 57, n°2, 2004. pp. 243-303. DOI : https://doi.org/10.3406/rhs.2004.2214; www.persee.fr/doc/rhs_0151-4105_2004_num_57_2_2214.

8.↑ Source : Jean-Pierre FLORENS, « ÉCONOMÉTRIE », Encyclopædia Universalis [en ligne], consulté le 23 mai 2021. URL : https://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/econometrie/

9.↑ Barbara Pabjan, “The use of models in sociology”, Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, vol. 336, issues 1–2, 2004, pp. 146–152. For the authors cited: Raymond Boudon, L’inégalité des chances, Fayard, 2010, p. 36 ff.

10.↑ Pierre Bourdieu, La distinction, Paris, Les Éditions de Minuit, 2016.

11.↑ See note 4.

12.↑ Raymond Boudon, op. cit.

13.↑ Some references on multi-agent models:

– Michael W. Macy and Robert Willer, “From Factors to Actors: Computational Sociology and Agent-Based Modeling”, Annual Review of Sociology, 2002, 28:143–66.

– Frédéric Amblard, Juliette Rouchier, Pierre Bommel, Franck Varenne and Denis Phan, “Évaluation et validation de modèles multi-agents”, in: Modélisation et simulation multi-agents : applications aux Sciences de l’Homme et de la Société, ed. Frédéric Amblard, Denis Phan, Paris, Hermes Science Publications, 2006, pp. 103–140.

– Federico Bianchi and Flaminio Squazzoni, “Agent-based models in sociology”, WIREs Computational

14.↑ Raymond Boudon, op. cit., p. 36.

15.↑ Ibid., p. 175.

16.↑ ibid., p. 190: “We have seen that, even if cultural inequalities are completely eliminated, the model generates considerable inequalities in access to education.”

17.↑ Pierre Livet, Denis Phan and Lena Sanders, “Diversité et complémentarité des modèles multi-agents en sciences sociales”, Revue française de sociologie, 2014/4 (vol. 55), pp. 689–729. For a more detailed presentation and illustration of Schelling’s model, see: https://www.gemass.fr/dphan/complexe/schellingfr.html.

18.↑ Hedström, Peter, and Peter Bearman, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Analytical Sociology, Oxford University Press, 2011, chapter 17.

19.↑ Granovetter, Mark. “Threshold Models of Collective Behavior”. American Journal of Sociology, vol. 83, n°6 (May 1978), The University of Chicago, p. 1420-1433.

20.↑ For an overview, see: Harold Kincaid, “Causation in the Social Sciences”. In BeeBee, H., Hitchcock, P., and Menzies, P. (Eds). The Oxford Handbook of Causation, Oxford University Press, 2009, chapter 36.

21.↑ See in particular: Luc Boltanski, De la critique. Précis de sociologie de l’émancipation, Gallimard, 2009; Dominique Méda, La mystique de la croissance. Comment s’en libérer, Flammarion, 2013; Eva Illouz and Edgar Cabanas, Happycratie – Comment l’industrie du bonheur a pris le contrôle de nos vies, Premier Parallèle, 2018.

22.↑ See the two previous notes.

23.↑ For instance, Mark Granovetter, an economic sociologist, starts from an individualist approach and seeks to integrate cultural elements.

24.↑ Max Weber, Essais sur la théorie de la science, Plon, 1965, p. 125-126. My emphasis.

25.↑ See, for example, Robert Lucas’s model, “Expectations and the Neutrality of Money”, Journal of Economic Theory, 4, 103–124 (1972), and Nancy Cartwright’s commentary, “The Vanity of Rigour in Economics: Theoretical Models and Galilean Experiments”, in Hunting Causes and Using Them, Cambridge University Press, 2007. See also Olof Bäckman and Christofer Edling, “Mathematics Matters: On the Absence of Mathematical Models in Quantitative Sociology”, Acta Sociologica, 1999, vol. 42, pp. 69–78: “each one of these assumptions can justly be contested, but the point we wish to stress here is that they are made explicit.”

26.↑ Mark Granovetter, Société et économie, Seuil, 2020. Link to Deirdre McCloskey’s interesting article, “The Rhetoric of Economics”, Journal of Economic Literature, vol. 21, no. 2 (June 1983), pp. 481–517. This article later gave rise to a book of the same name that develops the author’s thinking.

27.↑ In La question de la liberté and in French articles on this website.

28.↑ Luc Boltanski and Laurent Thévenot, De la justification. Les économies de la grandeur, Gallimard, 1991, p. 24: “This reflection on the symmetry between the languages of description or explanatory principles deployed by the social sciences and, on the other hand, the modes of justification or critique used by actors has made us particularly attentive to the tensions that inhabit sociology when it claims to reconcile a positivist conception of scientific neutrality with a requirement of social critique. For critical sociology then puts itself in the position of being unable to recapture the necessarily normative dimensions that underpin its contribution to the denunciation of social injustices, which inevitably leads it to insist unduly on the externality of science in order to ground the legitimacy of its practice.”

29.↑ Bernard Walliser, Comment raisonnent les économistes, Odile Jacob, 2011. My emphasis.

30.↑ Nancy Cartwright, Hunting Causes and Using Them: Approaches in Philosophy and Economics, Cambridge University Press, 2007. (note 22)

31.↑ Ibid.

32.↑ Jean-Michel Chapoulie, Enquête sur la connaissance du monde social, Anthropologie, histoire, sociologie, France-États-Unis 1950-2000, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2017.

33.↑ BeeBee, H., Hitchcock, P., and Menzies, P. (Eds). The Oxford Handbook of Causation, Oxford University Press, 2009.

34.↑ See in particular Bernard Walliser, op. cit.; Nancy Cartwright, Hunting Causes and Using Them: Approaches in Philosophy and Economics, Cambridge University Press, 2007; Nancy Cartwright, “RCTs, Evidence, and Predicting Policy Effectiveness”, in Harold Kincaid (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Social Science, Oxford University Press, 2012, pp. 298–318; Judea Pearl and Dana Mackenzie, The Book of Why. The New Science of Cause and Effect, Penguin Books, 2019.

35.↑ Pierre Bourdieu, Jean-Claude Chamboredon, Jean-Claude Passeron, Le métier de sociologue, La Haye, Mouton, 1983, p. 67.

36.↑ Bernard Walliser, op. cit.

37.↑Jean-Michel Chapoulie, op. cit.

38.↑ Ibid.

39.↑ I am following here the terminology used by Frédéric Amblard, Juliette Rouchier, Pierre Bommel, Franck Varenne and Denis Phan, op. cit.

40.↑ Ibid.

41.↑ Ibid.: “The claims to rigour made on behalf of statistical procedures are only rarely discussed by those who do not use this approach. Their mistrust of the statistical approach is more readily expressed in private conversations.”

42.↑ See in particular:

– Romeijn, Jan-Willem, “Philosophy of Statistics”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Section 3.

– Harold Kincaid, “Causation in the Social Sciences”, op. cit.

– Capel, Roland, Monod, Denis, Müller, Jean-Pierre. “De l’usage perverti des tests inférentiels en sciences humaines”. In: Genèses, 26, 1997. Représentations nationales et pouvoirs d’État, pp. 123–142; doi: 10.3406/genes.1997.1436.

43.↑ Bernard Walliser, op. cit.

44.↑ Morgan, Mary S. and Morrison, Margaret (eds.) (1999). Models as Mediators: Perspectives on Natural and Social Science. Cambridge University Press, p. 11.

45.↑Franck Varenne, op. cit. The aspects of representation of reality and heuristic interest, the instrumental aim of models, and the idea that a family of models can define what is meant by truth are developed in other texts.

46.↑ Franck Varenne, op. cit.

47.↑ Morgan, Mary S. and Morrison, Margaret, op. cit.

48.↑ Bernard Walliser, op. cit. The author identifies the following functions of models: iconic, syllogistic, empirical, heuristic, praxeological and rhetorical.